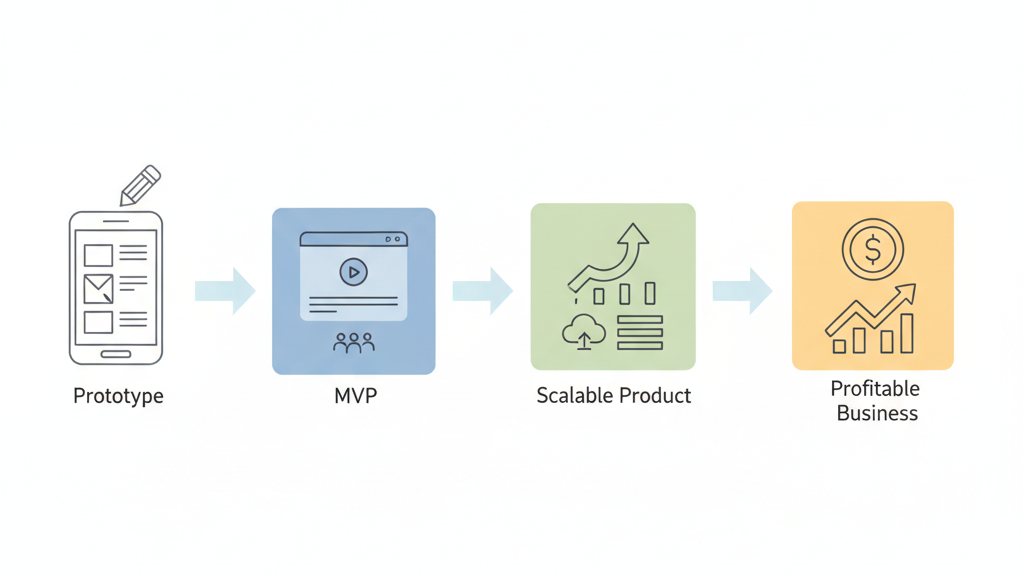

The MVP Roadmap: Scaling from Prototype to Profitable Product

An MVP roadmap isn’t about building fast it’s about building right so you don’t pay for bad decisions later. Most founders rush to launch, thinking speed equals progress. But the real challenge isn’t getting to market quickly. It’s getting there with a foundation that won’t collapse under your first hundred users. This guide will show you how to scale from prototype to profitable product without rebuilding everything from scratch.

What Most Founders Get Wrong About MVPs

Let’s clear something up: an MVP is not a half-baked product. It’s not the cheapest possible build. And it’s definitely not a “we’ll fix it later” situation.

I see this confusion all the time. Founders confuse speed with direction. They build feature-driven MVPs instead of problem-driven ones. They prioritize checking boxes over solving the actual problem their users face.

Here’s what happens: you ship fast, users show up, and suddenly your product can’t handle what they’re asking for. Not because you need more features, but because the foundation wasn’t built to grow. That’s hidden technical debt, and it’s expensive as hell to fix later.

The truth? Most MVPs fail to scale not because of what they include, but because of what founders didn’t think about before writing the first line of code.

Stage 1: Prototype Phase (Before the MVP Even Exists)

Your goal here isn’t to validate the product. It’s to validate the problem.

Too many founders skip this step entirely. They go straight from idea to development, burning time and money building something nobody asked for. A prototype isn’t your MVP—it’s your reality check.

What a Prototype Should Actually Prove

Your prototype needs to answer one question: does this problem hurt enough that someone will change their behavior to solve it?

Notice I didn’t say “will they pay for it” or “do they like the design.” Those questions come later. Right now, you’re testing whether the pain point is real and whether your approach makes sense.

Use Figma mockups, no-code tools, or clickable demos. Don’t write production code yet. You’re not building the thing—you’re proving the thing is worth building.

Questions to Answer Before Writing Real Code

- Can users articulate the problem you’re solving in their own words?

- Do they currently use a workaround, even if it’s clunky?

- When you show them your approach, do they immediately understand how it helps?

- Are they willing to test it, even in its roughest form?

If you’re getting “that’s interesting” instead of “when can I use this,” you’re not ready to build yet. And that’s okay. Better to learn it now than six months and $50K later.

Signals You’re Ready to Move Past a Prototype

You’ll know you’re ready when users start asking about features you haven’t shown them yet. When they’re mentally already using it and wondering about edge cases. When they’re frustrated that the prototype doesn’t actually work.

That’s your signal. That’s when you start building the real thing.

Stage 2: Building the MVP (The “Right First Version”)

Here’s where most founders make the critical mistake. They build the smallest possible app when they should be building the smallest scalable version.

There’s a difference. A huge one.

Choosing Core Workflows (Not Features)

Stop thinking in features. Start thinking in workflows.

A feature is “user can upload a photo.” A workflow is “user can create, edit, and share visual content with their team.” See the difference? One is a checkbox. The other is a complete thought.

Your MVP should include one to three core workflows that solve the main problem. That’s it. Not ten features scattered across five different use cases. Not every idea from your brainstorming session. Just the workflows that matter most.

Designing MVP Architecture with Future Growth in Mind

This is where founders panic and think I’m telling them to over-engineer everything. I’m not.

You don’t need microservices and enterprise-level infrastructure. But you do need to think about data structure, user permissions, and how features might connect later. You need modular thinking, even if your code is simple.

Ask yourself: if this works and we get 1,000 users next month, what breaks first? Then make sure that thing doesn’t break.

Deciding What Not to Build

This is harder than deciding what to build. Every feature sounds important when you’re in the weeds. But here’s the filter: if it doesn’t directly support a core workflow, cut it.

No social login unless authentication is part of the core value. No admin dashboard unless you’re managing user data as the primary function. No integrations unless your product literally doesn’t work without them.

Save that stuff for version two. Right now, you’re proving the concept, not showcasing your technical skills.

How Product Strategy Should Guide Tech Decisions

Your product strategy is simple at this stage: solve one problem really well for a specific group of people.

Every technical decision should support that strategy. If your developer says “we should use this framework because it’s faster” but it doesn’t align with how your users will actually use the product, push back. Speed doesn’t matter if you’re building the wrong thing quickly.

Understanding Technical Debt

Technical debt is what happens when you make a shortcut today that costs you time tomorrow. And the interest compounds fast.

What Technical Debt Really Means for Founders

Imagine you hardcode a feature to ship quickly. It works great for your first ten users. Then user eleven wants something slightly different, and you realize you have to rewrite the entire feature to accommodate them.

That’s debt. You saved time upfront, but now you’re paying it back with interest.

Good Debt vs Bad Debt

Not all debt is bad. Sometimes you need to ship fast to learn something important. That’s good debt—intentional, strategic, and planned for.

Bad debt is when you cut corners without realizing it, or when you ignore problems because “we’ll fix it later.” Later never comes. You just stack more features on top of a shaky foundation until something breaks.

How MVP Shortcuts Turn into Scaling Blockers

Here’s a real example: you build user profiles with a simple text field for “company name.” Works fine. Then a customer wants to invite teammates. Suddenly you need actual company objects, permissions, and relationships between users.

But your whole system was built around individual users. Now you’re looking at a complete rewrite of your user model, authentication system, and probably half your features.

That’s a scaling blocker. And it started with a tiny decision that seemed fine at the time.

Where Technical Debt Starts (And How to Avoid It Early)

Debt doesn’t usually come from bad developers. It comes from rushed decisions and unclear product thinking.

Common Causes

Hard-coded logic. You write specific rules for specific scenarios instead of building flexible systems. This seems faster, but every new scenario means more hardcoding.

Over-custom features for first users. Your beta customer wants something specific. You build it exactly how they want it. Then the next customer wants it completely differently, and your code can’t handle it.

No documentation or product logic clarity. You build features without writing down why they work that way. Six months later, nobody remembers the reasoning, and changing anything feels risky.

Ignoring data structure planning. You throw data into whatever format works today without thinking about how you’ll query it, update it, or scale it tomorrow.

Prevention Strategies

Modular thinking. Build features as independent pieces that connect, not as one giant tangled system. If you need to change one thing, it shouldn’t break three others.

Simple but flexible data models. Spend an extra day planning how data relates to each other. It feels slow now, but it’ll save you weeks later.

Product decisions before tech decisions. Always ask “what problem are we solving” before asking “how should we code this.” The technical solution should follow the product logic, not the other way around.

Stage 3: Early Traction & Validation

You’ve launched. Users are showing up. Now comes the tricky part: learning from them without breaking everything.

What Metrics Matter at This Stage

Forget vanity metrics. I don’t care about your total signups or page views. What matters:

- Activation rate: How many users complete the core workflow?

- Retention: Are people coming back, or is this a one-time thing?

- Time to value: How long does it take a new user to get their first win?

These metrics tell you if your product actually works. Everything else is just noise.

Using Feedback to Refine Workflows

Listen to user feedback, but read between the lines. When someone says “I wish you had feature X,” what they’re really saying is “I’m trying to accomplish Y and I can’t.”

Your job isn’t to build every requested feature. It’s to understand the underlying need and decide if it fits your core workflows. Sometimes the answer is yes. Often, it’s no.

When to Refactor vs When to Ship Fast

If the debt is blocking new users from succeeding, refactor. If it’s annoying but not critical, add it to the list and keep shipping.

The rule: fix things that hurt growth, defer things that are just inefficient.

Avoiding Feature Creep from Early Customers

Your first customers will have opinions. Strong ones. They’ll want custom features, special workflows, and integrations with their weird internal tools.

Be careful. You’re not building custom software for them. You’re building a product that serves a market. If their request aligns with your core workflows and benefits other users, great. If it’s specific to their unique situation, politely decline.

You can’t be everything to everyone. Especially not at this stage.

Stage 4: Scaling the MVP into a Real Product

This is where your MVP either becomes a real product or collapses under its own weight.

Signals Your MVP Is Ready to Scale

You’ll know you’re ready when:

- Core workflows are solid and users consistently succeed with them

- You have clear patterns in how people use the product

- Retention is strong enough to justify growth investment

- You’re turning away features because they don’t fit, not because you can’t build them

If you’re still figuring out product-market fit, you’re not ready to scale. Don’t rush this.

Scaling Features vs Scaling Infrastructure

These are different problems. Scaling features means adding new workflows and capabilities. Scaling infrastructure means making sure your systems can handle more load.

Do them in the right order. If your product doesn’t work well for 100 users, it won’t magically work better for 10,000. Fix the product first, then worry about infrastructure.

How to Prioritize Roadmap Items

Every item on your roadmap should answer one question: does this make our core workflows better, or does it add new workflows?

Making core workflows better always wins. Adding new workflows should only happen when the existing ones are really solid.

Don’t get distracted by shiny features. Stay focused on what actually moves the needle.

Aligning Product Strategy with Business Model

How you make money should influence what you build. If you charge per user, focus on features that make teams want to invite more people. If you charge for usage, focus on features that encourage more frequent engagement.

This sounds obvious, but I’ve seen countless products build features that don’t support their business model at all. Don’t be that founder.

Product Roadmap vs Feature Roadmap (Critical Difference)

Most teams have feature roadmaps. They list out what they’re building and when. It’s a checklist of functionality.

Product roadmaps are different. They focus on outcomes, not outputs.

Feature Roadmap (What Most Teams Do)

- Q1: Build user profiles

- Q2: Add messaging

- Q3: Build notification system

- Q4: Add analytics dashboard

This tells you what you’re building, but not why. It’s a construction plan, not a strategy.

Product Roadmap (What Scales)

- Q1: Enable users to establish credibility and trust

- Q2: Facilitate meaningful connections between users

- Q3: Keep users engaged without overwhelming them

- Q4: Help users understand their impact and progress

Notice the difference? Each quarter focuses on an outcome. The features you build are just the means to that end.

Outcome-Based Planning

When you plan around outcomes, you stay flexible. If user profiles don’t establish credibility the way you thought, you can try something else. You’re not married to the feature—you’re committed to the outcome.

This is how you avoid building the wrong things for the right reasons.

User Journey Thinking

Map out how users move through your product. Where do they get stuck? Where do they succeed? Where do they leave?

Your roadmap should address these moments, not just add random features because they sound cool.

Long-Term System Flexibility

Every feature you build should make future features easier, not harder. If adding something new requires rewriting old code every time, your system isn’t flexible enough.

Build with the assumption that you don’t know exactly what you’ll need next year. Because you don’t.

When (and How) to Pay Down Technical Debt

At some point, you’ll need to stop adding features and fix the foundation. Here’s how to know when.

Signs Debt Is Hurting Growth

- New features take way longer to build than they should

- Bugs appear in unexpected places when you change something

- Your team is scared to touch certain parts of the codebase

- You’re losing users because things are slow or breaking

If any of these are true, it’s time to address the debt.

How to Plan Refactoring Without Stopping Development

Don’t stop everything to fix debt. You’ll lose momentum and probably run out of money.

Instead, allocate time. Maybe 20% of each sprint goes to debt reduction. Maybe one week per month is “foundation week.” Find a rhythm that lets you improve the system while still shipping new value.

Budgeting Time for Cleanup

Estimate how long the refactoring will take, then double it. Seriously. Debt is always worse than it looks from the outside.

And make sure you’re fixing root causes, not symptoms. Patching one bug doesn’t help if the underlying system is broken.

Communicating This to Non-Technical Stakeholders or Investors

Non-technical people don’t care about your code architecture. They care about business outcomes.

Frame debt reduction in terms they understand: “We need to invest two weeks now to make sure we can ship features twice as fast for the next six months.” Or: “If we don’t fix this, we’ll start losing customers because the product will be too slow.”

Make it about growth and risk, not about clean code.

Real-World MVP Scaling Mistakes (Founder Lessons)

Let’s talk about the mistakes I see over and over again.

Building for Edge Cases Too Early

Your first user has a weird edge case. You build a whole feature to handle it. Then you realize 95% of users don’t need that feature, and it’s complicating everything else.

Edge cases are called edge cases for a reason. Handle them manually at first. Only build for them when they become common cases.

Rewriting Instead of Improving

Something’s broken, so you decide to rebuild it from scratch. You think it’ll be faster and cleaner.

It never is.

Rewrites take longer than you expect, introduce new bugs, and distract you from actual product work. Unless your code is completely unsalvageable, improve it incrementally instead of starting over.

Scaling Users Before Scaling Systems

You get press coverage. Users flood in. Your product breaks under the load. Half of them leave and never come back.

This is preventable. If you’re about to run a growth campaign, stress test your systems first. Make sure they can handle 10x your current traffic. Then run the campaign.

Letting Tech Dictate Product Direction

Your developer loves a particular technology, so you build features around what it’s good at instead of what users need.

This is backwards. Technology serves the product, not the other way around. If your tech choices are limiting your product, change the tech.

A Simple MVP Roadmap Framework (Step-by-Step)

Here’s a framework you can actually use:

- Problem Validation

Talk to users. Understand their pain. Make sure it’s real and urgent enough that they’ll change behavior to solve it. - Workflow Definition

Map out the one to three core workflows that solve the problem. Don’t think about features yet—think about what users need to accomplish. - MVP Architecture Planning

Spend a few days planning your data models, user flows, and technical approach. This isn’t over-engineering—it’s thinking before building. - Lean Build

Build the minimum version that supports those core workflows. Cut ruthlessly. If it doesn’t directly enable the workflow, save it for later. - Feedback Loops

Get users in front of your product. Watch them use it. Listen to what they struggle with. Ignore feature requests and focus on workflow problems. - Strategic Scaling

Once core workflows are solid, add new capabilities one at a time. Make sure each addition makes sense strategically, not just tactically. - Debt Management Checkpoints

Every month or quarter, assess your technical debt. Fix the things that are slowing you down. Defer the things that are just annoying.

This isn’t complicated. But it requires discipline and patience. Two things most founders struggle with.

How Founders Should Think About MVPs Long-Term

Your MVP isn’t a launch event. It’s a learning system.

The point isn’t to ship something and call it done. The point is to ship something that teaches you what to build next. And then the next thing after that.

Why “Temporary” Decisions Are Rarely Temporary

Every time you say “we’ll fix it later,” there’s a 70% chance you won’t. Later never comes because you’re busy building new stuff.

So assume that temporary decisions might become permanent. Make them carefully.

Building Optionality into Your Product

The best MVPs leave room to grow in multiple directions. They don’t lock you into one specific path.

Think about your product as a platform, even if it’s simple. What might you build on top of it someday? How can you structure things now to make that easier later?

You don’t need to build for every possible future. But you should avoid building in ways that close off obvious opportunities.

Final Takeaway: Build for Progress, Not Panic

Most founders build in panic mode. They rush to launch, race to add features, and scramble to fix things when they break.

This approach burns you out and produces mediocre products.

Instead, build for progress. Make deliberate decisions. Think about product strategy before tech implementation. Cut features ruthlessly. Focus on workflows, not checklists.

Yes, you need to move fast. But moving fast in the wrong direction doesn’t help. Better to move steadily in the right direction than to sprint toward a cliff.

Your MVP roadmap isn’t about speed. It’s about building a foundation that can grow without collapsing. It’s about making smart tradeoffs early so you don’t pay for them exponentially later.

Build calmly. Build intentionally. Build something that can actually scale.