How Does Software Work?

Software works by taking user input, processing it through defined rules, and producing an output. Behind the scenes, it follows instructions, manages data, and communicates with systems to complete tasks reliably and consistently.

What Is Software, Really?

At its simplest, software is a set of instructions that tells a computer what to do. That’s it. No mystery, no magic.

Think about it this way: hardware is the physical device you can touch your phone, your laptop, the screen you’re reading this on. Software is the invisible layer that makes that hardware useful. Without software, your expensive smartphone would just be a fancy paperweight.

Why does software exist? Because hardware alone can’t do anything meaningful. Your computer’s processor is incredibly powerful, but it doesn’t know what to do with that power until software gives it instructions. Your phone’s screen can display millions of colours, but it needs software to decide what to show you.

Everyday examples are everywhere. The weather app on your phone? Software. The spreadsheet program you use for budgeting? Software. The browser displaying this article right now? Software. Even the calculator app you use for quick maths that’s software too.

Software exists in everything digital. Your car’s navigation system, your smart TV, your fitness tracker, even your microwave’s timer they all run on software. It’s become so embedded in daily life that we rarely stop to think about how it actually works.

The Core Idea Behind All Software

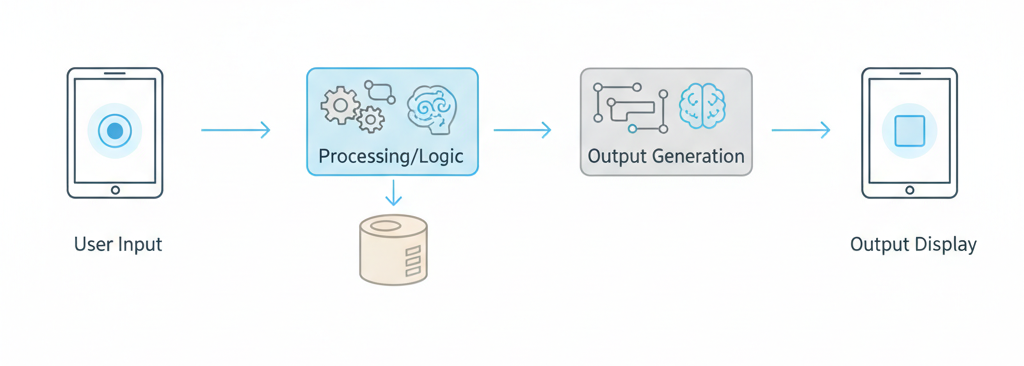

Here’s the fundamental principle that every piece of software follows, from the simplest calculator to the most complex business system: Input → Process → Output.

Every single thing software does can be broken down into these three steps. You give it something (input), it does something with that information (process), and it gives you something back (output).

Let me give you a real-life analogy that has nothing to do with technology. Imagine you’re following a recipe to bake a cake. The ingredients are your input. The recipe instructions are your process the rules you follow. The finished cake is your output. Software works exactly the same way.

When you search for something on a search engine: your search terms are the input, the search algorithm processing millions of web pages is the process, and the list of results is the output. Input → Process → Output.

When you send a text message: your typed message is the input, the app packaging and sending that message through networks is the process, and your friend receiving the message is the output. Input → Process → Output.

This model still applies today, even though software has become incredibly sophisticated. Whether it’s a cutting-edge AI system or a simple note-taking app, the fundamental logic remains the same. The processes might be more complex, the inputs more varied, the outputs more sophisticated—but the pattern never changes.

How Software Receives Input

Software needs information to work with, and that information comes from inputs. There are two main types: things you do deliberately, and things that happen automatically.

User actions are the most obvious. Every time you click a button, type on your keyboard, tap your screen, scroll through a page, or speak a voice command, you’re providing input. The software is constantly watching for these actions, waiting to respond.

But not all inputs come from direct user actions. Automatic inputs happen without you doing anything. Your phone’s alarm goes off at 7 AM—that’s a timer triggering input. Your fitness tracker detects you’ve been sitting too long—that’s a sensor providing input. Your email app checks for new messages every few minutes that’s a scheduled signal creating input.

Here’s something important: software must validate input. It can’t just accept anything you throw at it. If you’re filling out a form that asks for your email address and you type in “banana”, the software needs to recognise that “banana” isn’t a valid email address and let you know.

This validation happens constantly, though you usually only notice it when something goes wrong. When a website tells you “Please enter a valid phone number” or “Password must be at least 8 characters”, that’s input validation in action.

What happens when input is missing or wrong? The software has to make a decision. Sometimes it’ll ask you to provide the correct input. Sometimes it’ll use a default value instead. Sometimes it’ll simply refuse to proceed until you fix the problem. Good software handles this gracefully. Poor software crashes or behaves unpredictably.

How Software Processes Information

Once software has its input, it needs to do something with it. This is where the interesting part happens—the processing.

Processing is really just following rules and making decisions based on those rules. Let me explain this in plain English, no technical language needed.

Imagine you’re using a calculator app and you type “5 + 3”. The software’s rules say: “When I see two numbers with a plus sign between them, I add those numbers together.” So it follows that rule and gives you 8. That’s processing.

Or think about a thermostat app. You set the temperature to 22 degrees. The app checks the current temperature—let’s say it’s 19 degrees. The rule is: “If current temperature is below target temperature, turn on the heating.” The app follows that rule. That’s decision-making inside software.

Every piece of software contains hundreds, thousands, sometimes millions of these rules. “If this, then do that.” “When this happens, respond this way.” “Take this information and transform it like so.” The software follows these rules in sequence, step by step, working through its processing flow.

Why does software behave consistently? Because rules don’t change on their own. If you use a calculator and type “5 + 3” a hundred times, you’ll get 8 every single time. The software isn’t guessing or being creative—it’s following the exact same instructions it followed last time.

This consistency is both software’s greatest strength and its limitation. It’s incredibly reliable at doing what it’s programmed to do, but it can’t adapt or think creatively beyond its rules. When you encounter unexpected behaviour in software, it’s usually because the rules didn’t account for your specific situation.

Where Software Stores Data

Software needs memory, just like humans do. It needs to remember what you typed, what choices you made, what you were doing last time, and what it needs to do next.

There are two main types of data storage in software: temporary and permanent.

Temporary data is information the software only needs right now, in this moment. When you’re typing a message and haven’t sent it yet, that text is in temporary storage. When you’re scrolling through a webpage and it loads more content as you scroll, that content is temporarily stored. If you close the app or refresh the page, this temporary data disappears.

Permanent data is information the software saves for later. Your saved documents, your account preferences, your app settings, your photo library these are all permanently stored. Even if you close the app, turn off your device, or come back weeks later, this data is still there.

There’s also a distinction between local storage and central storage. Local storage means the data lives on your specific device your phone, your laptop, whichever device you’re using right now. Central storage means the data lives on a server somewhere else, and your device accesses it when needed. We covered this in detail when we talked about syncing, but the basic idea is that central storage lets you access your data from multiple devices.

Why does software remember things? Convenience and functionality. Imagine if you had to reconfigure every app setting every single time you opened it. Imagine if your browser didn’t remember your login information. Imagine if your music app didn’t remember where you left off in a playlist. Storage makes software useful.

What happens when data is deleted? It depends on the type of deletion. Sometimes deleted data is just marked as “deleted” but still exists on the device until it’s overwritten. Sometimes it’s immediately erased. Sometimes it’s moved to a “recycle bin” or “trash” where it can be recovered. The permanence of deletion varies by software and by situation.

How Software Produces Output

After software has received input, processed it according to its rules, and potentially stored or retrieved data, it needs to give you a result. That’s the output.

Visual output is what most people think of first. This is everything you see on your screen: text appearing as you type, images loading on a webpage, notifications popping up, charts and graphs displaying information, videos playing, buttons changing colour when you hover over them. All of this is software producing visual output.

But not all output is visual. Background output happens without you necessarily seeing it. When your email app syncs new messages in the background, that’s output. When your cloud storage app uploads a file while you’re doing something else, that’s output. When your fitness tracker updates your step count, that’s output happening behind the scenes.

Why do outputs differ by device? Because different devices have different capabilities. A smartwatch has a tiny screen, so software running on it produces more compact output. A desktop computer has a large screen, so software can show more detailed information. A speaker has no screen at all, so software produces audio output instead. The same app might produce different outputs depending on where it’s running.

There’s also the concept of feedback loops. Good software doesn’t just produce output and disappear—it responds to how you interact with that output. You click a button, and it changes colour to show you it registered your click. You submit a form, and you get a confirmation message. You make an error, and you see a helpful error message. This back-and-forth between you and the software creates a conversation of sorts.

How Different Parts of Software Work Together

Software isn’t one monolithic block. It’s organised into different layers, each with its own job. Understanding this helps explain why software can be both simple to use and incredibly complex under the surface.

The interface layer is what you see and interact with. This is the buttons, menus, forms, images, and text. It’s designed to be understandable and usable. Everything in this layer exists to help you communicate with the software. When you click “Save”, that’s you interacting with the interface layer.

Behind that is the processing layer. This is where the actual work happens—where rules are followed, decisions are made, and data is manipulated. When you click that “Save” button, the interface layer tells the processing layer, “The user wants to save.” The processing layer then does the actual work of saving your data.

Deeper still is the data layer. This is where information is stored and retrieved. The processing layer might tell the data layer, “Store this information,” or “Retrieve that information for me.” The data layer handles the actual storage mechanics.

Why does this separation matter? Because it allows different parts of the software to change independently. You could redesign the entire interface without changing how the processing works. You could improve how data is stored without changing the interface. This modular approach makes software easier to build, maintain, and update.

When you use any app, all three layers are working together simultaneously. You’re only aware of the interface layer, but the other two are constantly active, doing their jobs invisibly.

How Software Communicates With Other Systems

Here’s something that surprises many people: most software doesn’t work alone. Apps and programs are constantly communicating with other systems, exchanging information, requesting services, and responding to requests.

What does system communication mean? It’s software talking to other software. Your weather app talks to a weather service to get current conditions. Your banking app talks to your bank’s servers to check your balance. Your social media app talks to dozens of different systems to load your feed, show advertisements, send notifications, and more.

This communication follows a simple pattern: requests and responses. One piece of software sends a request: “I need this information” or “Please do this action.” Another piece of software receives that request, processes it, and sends back a response: “Here’s the information you asked for” or “I’ve completed that action.”

Let me give you an everyday example. When you search for a restaurant on a maps app, here’s what happens behind the scenes: Your app sends a request to the maps service: “Show me restaurants near this location.” The maps service processes that request—it searches its database, finds relevant restaurants, and sends back a response with the results. Your app receives that response and displays it on your screen. All of this happens in seconds.

Why does software rarely work alone? Because specialisation is more efficient. Instead of every weather app maintaining its own weather stations and meteorology team, they all connect to specialised weather services. Instead of every shopping app building its own payment processing system, they connect to payment services. Software works better when it focuses on what it does best and relies on other systems for everything else.

How Software Runs on Different Devices

You might have noticed that the same app behaves slightly differently on your phone versus your laptop. Or that some software only works on certain devices. There’s a reason for this.

Software is designed to run on specific types of devices, and those devices have different capabilities, different screen sizes, different ways of interacting, different levels of processing power. The software has to adapt to these differences.

This is where operating systems come in. Your phone has an operating system (like iOS or Android), and your laptop has an operating system (like Windows or macOS). The operating system is like a translator between the software and the hardware. It provides a consistent way for software to communicate with all the different hardware components—the screen, the keyboard, the processor, the storage, the network connection.

When software is built “for iOS” or “for Windows”, what that really means is it’s built to work with that specific operating system. It speaks the language that operating system understands.

Compatibility is simply whether software can run on a particular system. Some software is compatible with multiple operating systems—you can run it on your iPhone and your Windows laptop. Other software only works on one system. This isn’t arbitrary—it’s a practical reality of how different systems work.

Why are updates necessary? Partly because operating systems themselves get updated. When your phone’s operating system updates, software has to adapt to those changes. Updates also add new features, fix problems, and improve compatibility with newer devices. Software that never updates eventually stops working as the world around it changes.

How Software Updates Work

Speaking of updates, let’s talk about what actually happens when you update software.

Updates exist for three main reasons: fixing problems, adding features, and maintaining compatibility. Sometimes an update does all three at once.

What changes during an update? The instructions the software follows. Remember those rules we talked about earlier? Updates can modify those rules, add new rules, or remove outdated rules. Updates can also change how the software looks, how it stores data, and how it communicates with other systems.

Here’s what happens technically: the update downloads new files that replace or add to the existing software files. Your device installs these new files, and the next time you open the software, it’s running the updated version with the new instructions.

Why do updates sometimes break things? Because changing rules can have unintended consequences. Imagine you have a rule that says, “Save the user’s preference as Option A or Option B.” Then an update changes this to include Option C. But some older part of the software wasn’t updated and still only expects A or B. Now there’s a conflict, and things might break.

This is why software developers test updates extensively before releasing them—but they can’t test every possible scenario. Sometimes problems only appear when millions of people start using the update in ways the developers didn’t anticipate.

When updates do break things, most software has a way to roll back—to revert to the previous version whilst they fix the problem. Or they’ll quickly release another small update that fixes the issue the previous update caused. You might have noticed this: sometimes you get updates very close together, one after another. That’s usually fixing problems the previous update introduced.

Why Software Sometimes Fails

Let’s be honest—software fails. Apps crash, programs freeze, websites go down, features stop working. Understanding why this happens makes it less frustrating when it does.

Bugs are mistakes in the software’s rules. Imagine a rule that says, “If the user’s age is greater than zero, proceed.” Sounds fine, right? But what if someone enters their age as text instead of a number? The software tries to check if “twenty-five” is greater than zero, doesn’t know how to handle that, and crashes. That’s a bug—an oversight in the rules.

Bugs are inevitable because software is written by humans, and humans make mistakes. Even with extensive testing, some bugs slip through because they only appear in specific, unusual circumstances that weren’t tested.

Data issues cause failures too. Software might be expecting data in a certain format, and if it receives data in a different format, it doesn’t know what to do. Or the data might be corrupted—damaged in some way. Or it might simply be missing when the software expects it to be there.

External dependencies are another common failure point. Remember how software communicates with other systems? If one of those other systems is down or slow, the software depending on it can fail or perform poorly. Your app might be working perfectly, but if the service it’s trying to connect to is having problems, you’ll experience those problems too.

Why is failure unavoidable? Because software operates in a complex, unpredictable environment. There are too many possible combinations of user actions, data states, network conditions, device types, and external system behaviours to test and account for everything. Good software minimises failures and handles them gracefully when they do occur, but eliminating them entirely is impossible.

How Software Improves Over Time

Despite all the ways software can fail, it generally gets better over time. There’s a fascinating process of continuous improvement happening behind the scenes.

Learning from usage is a big part of this. Developers track how people actually use their software—which features are popular, where users get stuck, what actions lead to crashes. This real-world usage data is invaluable for understanding what works and what doesn’t.

Many apps send anonymous usage statistics back to the developers. When the app crashes, it might ask if you want to send a crash report. These reports contain information about what was happening when the crash occurred, helping developers identify and fix the problem.

Feedback loops work through multiple channels. Direct user feedback—reviews, support tickets, feature requests—tells developers what users want and what’s frustrating them. Indirect feedback comes from usage patterns. If everyone abandons a feature after trying it once, that’s feedback too, even if nobody explicitly complained.

Performance optimisation happens gradually. Developers identify the slow parts of their software and find ways to make them faster. They reduce how much memory the software uses. They make it start up quicker. They make features respond more quickly. Each small improvement adds up over time.

Feature evolution is the most visible form of improvement. New capabilities get added, existing features get refined, outdated features get removed. This evolution is guided by user needs, technological advances, and competitive pressures. Software that doesn’t evolve becomes obsolete.

The result is that software you use today is almost certainly better than the same software was a year ago, and it’ll probably be even better a year from now.

Common Myths About How Software Works

Let’s clear up some widespread misconceptions about software.

Myth: “Software thinks on its own.” No, it doesn’t. Software follows rules. It can follow incredibly complex rules, it can simulate intelligent behaviour, but it’s not actually thinking. Every action it takes was anticipated and programmed by its developers. Even AI systems that seem to “learn” are really just following sophisticated rules for pattern recognition and decision-making.

Myth: “More features equals better software.” Actually, more features often makes software worse. Each additional feature adds complexity, increases the chance of bugs, makes the software harder to use, and slows down performance. The best software often has fewer features, executed brilliantly, rather than many features executed poorly.

Myth: “Software is always accurate.” Software is only as accurate as its rules and its data. If the rules contain mistakes, the software will make mistakes. If the data is wrong, the software will produce wrong results. “The computer said so” doesn’t mean it’s correct—it means that’s what the software calculated based on what it was given.

Myth: “Updates only add features.” Updates do much more than add features. Most updates focus on fixing bugs, improving security, enhancing performance, and maintaining compatibility. Feature additions are often the least important part of an update, though they’re the most visible and get the most attention.

Understanding these realities helps set appropriate expectations for what software can and can’t do.

How Modern Software Is Different From Old Software

Software has changed dramatically over the past couple of decades. If you used computers in the 1990s or early 2000s, you’d notice some fundamental differences in how software works today.

Always-connected systems are now the norm. Older software worked entirely on your device with no internet connection required. Modern software assumes you’re connected and relies on that connection constantly. This enables syncing, real-time collaboration, cloud storage, and continuous updates, but it also means software stops working properly when your connection drops.

Continuous updates have replaced the old model of buying software in a box and using that same version for years. Modern software updates itself automatically, sometimes daily. You’re always running a relatively recent version. The advantage is you get improvements and fixes constantly. The disadvantage is the software you knew yesterday might work slightly differently today.

Cloud-based logic has moved much of the processing from your device to remote servers. Older software did all its work on your device. Modern software often sends your data to a server, processes it there, and sends back the results. This allows software to handle more complex tasks and enables features that would be impossible on your device alone, but it creates dependencies on external systems.

Cross-device experiences are expected now. Older software was tied to a single computer. Modern software works across your phone, tablet, laptop, and maybe even your watch or TV. Everything syncs, and you can pick up where you left off on any device. This convenience requires sophisticated synchronisation systems and cloud infrastructure that didn’t exist in earlier eras.

These changes have made software more powerful and more convenient, but also more complex and more dependent on infrastructure beyond your control.

Why Understanding How Software Works Matters

You might be wondering: why should I care about any of this? I just want my apps to work.

Fair question. Here’s why this understanding is valuable:

Better user decisions come from knowing how things work. When choosing between apps, you’ll better understand what different features mean and what trade-offs you’re making. You’ll know which concerns are legitimate and which marketing claims are exaggerated.

Smarter product expectations prevent frustration. When you understand that software follows rules and depends on external systems, you’ll have realistic expectations about what it can do. You’ll be less frustrated when it fails in understandable ways, and more impressed when it handles edge cases smoothly.

Reduced frustration happens when you can diagnose problems yourself. If an app isn’t working, understanding the basic input-process-output flow helps you identify where the problem might be. Is it your input? Is it your internet connection? Is it the external service the app depends on? You can often solve problems without needing support.

Digital literacy advantage matters in the modern world. We interact with software dozens of times a day. Understanding how it works makes you a more capable user, better equipped to learn new tools, and more confident in digital environments. This translates to practical advantages in work and daily life.

You don’t need to know how to build software to benefit from understanding how it operates. Just like you don’t need to be a mechanic to be a better driver, but knowing how cars work generally makes you a more competent and confident driver.

Wrap Up

So there you have it how software works, explained without jargon or technical complexity.

At its core, software is remarkably simple: it takes input, processes that input according to defined rules, and produces output. Everything else the layers of complexity, the communication between systems, the storage of data, the updates and improvements all builds on this fundamental logic.

Software isn’t magic, it’s not intelligent, and it’s not mysterious. It’s a set of instructions being followed consistently and reliably. When you understand this, software becomes less of a black box and more of a tool you can truly master.

The beauty of software is that whilst the underlying principles remain constant, the applications are endless. The same input-process-output logic powers a simple calculator and a sophisticated video editing suite. The same rules-based processing drives a weather app and a banking system.

Modern life is saturated with software, and that’s only going to increase. The more you understand about how it works, the more effectively you can use it, the better decisions you can make about it, and the less intimidating the digital world becomes.

You don’t need to become a developer or memorise technical terms. You just need to remember: input, process, output. Rules being followed. Data being stored and retrieved. Systems communicating with each other. That simple framework explains almost everything software does.

[…] management software works by tracking stock levels in real time, recording every movement of items, and updating data […]